wElcOMe To The eXHuLME© Website

Diggin the oLd Hulme, Manchester

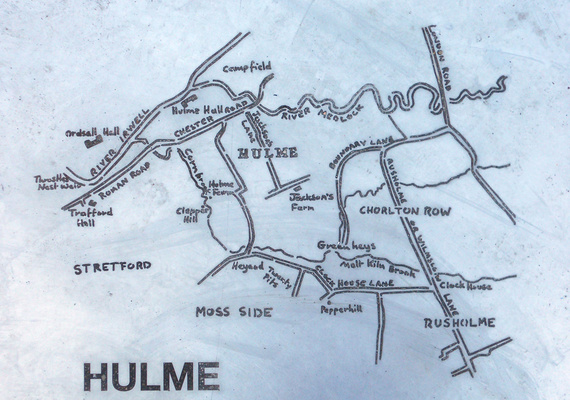

Hulme (pronounced hyoom) is an ex-industrial suburb to the south of the City of Manchester, England. It is known chiefly for its social and economic decline in the 1960s, 70s and 80s, and its subsequent redevelopment in the 1990s, as part of one of Europe's biggest urban regeneration projects. The area received its name from the Danish expression for a small island surrounded by water or marshland which, in fact, it probably was when it was first settled by Norse invaders from Scandinavia. It was evidenced as a separate community south of the River Medlock from Manchester in 15th century map prints. Until the 18th century it remained a solely a farming area, and pictures from the time show an idyllic scene of crops, sunshine and country life. The area remained entirely rural until the Bridgewater Canal was cut and the Industrial Revolution swept economic change through the neighbouring district of Castlefield where the Dukes' canal terminated, and containerised transportation of coal and goods rose as an industry to support the growing textile industries of Manchester. It was this supply of cheap coal from the Dukes' mines at Worsley that allowed the textile industry of Manchester to grow. The Industrial Revolution eventually brought development to the area, and jobs to the urban poor in Hulme carrying coal from the 'Starvationer' (very narrow canal boats), to be carted off along Deansgate. Many factories (known locally as mills) and a railway link to Hulme soon followed, and thousands of people came to work in the rapidly expanding mills in the city. Housing therefore had to be built rapidly, and space was limited. Hulme's growth in many ways was a "victim of its' own success", with hastily built, low-quality housing interspersed with the myriad smoking chimneys of the mills and the railway, resulting in an extremely low quality of life for residents. Reports of the time suggest that even in an extremely residential area such as Hulme, at times air quality became so low that poisonous fumes and smoke literally "blocked out the sun" for long periods. The number of people living in Hulme went up 50-fold in the first half of the 19th century and the rapid building of housing to accommodate the population explosion meant the living conditions were of extremely low standard, with sanitation non-existent and rampant spread of disease. By 1844, the situation had grown so serious that Manchester Borough Council (now Manchester City Council) had to pass a law banning further building. However, the thousands of "slum" homes that were already built continued to be lived in, and many were still in use into the first half of the 20th century.

Ouerholm and Noranholm were recorded in 1226 and Norholm in 1227. These are thought to be variations of Overhulm and Netherhulm, although recorded earlier. The surname de Hulm is known from records of 1246, 1273, 1277, 1285, 1332 and 1339 and del Hulme from 1284. There are other early Hulm(e)s/Holm(e)s from which they might have received their surnames (by Warrington and Lancaster, for example). In 1310 there is a mention of "the manor of Hulm with the appurtenances, near Mamcestre".

In 1322 in the records of rents of the lands of the recently executed enemy of the King and rebel Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, the following are mentioned as in the Wapentake of Salfordshire: "Geoffrey de Hulme holds half a ploughland in Hulme and renders yearly 5s[hillings]." or, in an alternate version: "Geoffrey de Hulme holds one ploughland in Hulme by the service of 5s. yearly at the 4 terms for all." and "John le Ware holds one ploughland in Hulme by the service of 5s. yearly at the 4 terms." In 1324 there is a record of "... ; farm of the land of Geoffrey de Hulme in Hulme which Jordan the dean formerly held in Overhulm and Netherhulm 5s ; ..."

In 1440 there is a mention of the manor of Hulme and land exchanged for 200 pounds of silver: "Between William de Byrom, Henry de Par and John Hepe, late of Hulme, plaintiffs, and Ralph de Prestwich, deforciant of the manor of Hulme with the appurtenances, and of 9 messuages, 300 acres of land, 100 acres of meadow, 500 acres of pasture, and 100 acres of wood in Mamcestre, Crompton and Oldom.

Hulme was evidenced as a separate community south of the River Medlock from Manchester in 15th century map prints. Christopher Saxton included Holme in his map of Lancashire of 1577 on the south banks of the Medlock and the Irwell where they joined. Trafford was placed on the south bank of the Irwell to the south-west, Wordsall across the Irwell to the north-west and Manchester across the Medlock to the north.[7] Hulme Hall was close to the River Irwell on a site near where St George's Church was later built. Until the 18th century the area remained agricultural, and pictures from the time show an idyllic scene of crops, sunshine and country life. The area remained entirely rural until the Bridgewater Canal was cut and the Industrial Revolution swept economic change through the neighbouring district of Castlefield where the Duke of Bridgewater's canal terminated, and containerised transportation of coal and goods rose as an industry to support the growing textile industries of Manchester. It was this supply of cheap coal from the Duke's mines at Worsley that allowed the textile industry of Manchester to grow.

The Industrial Revolution brought development to the area, and jobs to the poor, carrying coal from the 'starvationers' (very narrow canal boats), to be carted off along Deansgate.

Many cotton mills and a railway link to Hulme soon followed, and thousands of people came to work in the rapidly expanding mills in the city. The number of people living in Hulme multiplied 50-fold during the first half of the 19th century. Housing had to be built rapidly, and space was limited, which resulted in low-quality housing interspersed with the myriad smoking chimneys of the mills and the railway. Added to the lack of sanitation and rampant spread of disease, this gave an extremely low quality of life for residents. Reports of the time suggest that at times the air quality became so poor that poisonous fumes and smoke literally "blocked out the sun" for long periods.

In the Irish Poor Report of 1836 the Deputy Constable of the Township of Manchester, Joseph Sadler Thomas, found that the Irish were so fiercely neighborly in Little Ireland (located on the other side of the River Medlock, just north of Hulme Ward) and the larger Irish area of Angel Meadow (north-east of Victoria Station, on the other side of central Manchester from Hulme) that: "if a legal execution of any kind is to be made, either for rent or debt, or for taxes, the officer who serves the process almost always applies to me for assistance to protect him; and, in affording that protection, my officers are often maltreated by brickbats and other missiles".

The Salutation pub on Higher Chatham Street, where Charlotte Brontë began to write Jane Eyre; the pub was a lodge in the 1840s

Hulme Hall was demolished in 1840 with the construction of the Bridgewater Canal. By 1844, the situation had grown so serious that Manchester Borough Council had to pass a law banning further building. However, the thousands of "slum" homes that were already built continued to be lived in, and many were still in use into the first half of the 20th century.

Friedrich Engels was the heir of a German cotton manufacturer who had come to work for the Ermen & Engels factory in Weaste, Salford, three miles from Hulme though he worked in the firm's offices in Manchester. He made Little Ireland infamous throughout the world as a disastrous slum despite it being relatively short-lived (a little over 30 years) and other areas of Manchester having worse housing, poverty and disease. Little Ireland was a small slum between Oxford Road, the Medlock and the railway serving Oxford Road Station, mainly inhabited by Irish immigrant workers. Described at length by Engels, he estimated that there was one inaccessible privy for every 120 residents. "The cottages are old, dirty and of the smallest sort, the streets uneven, fallen into ruts and in part without drains or pavement; masses of refuse, offal and sickening filth lie among standing pools in all directions; the atmosphere is poisoned by the effluvia from these, and laden and darkened by the smoke of a dozen tall factory chimneys. A horde of ragged women and children swarm about here, as filthy as the swine that thrive upon the garbage heaps and in the puddles." Reinforcement of the Medlock to protect the factories raised the level of the river above the surrounding residential hovels leading to frequent flooding with filthy river water. Hulme was also described by Engels: "the more thickly built-up regions chiefly bad and approaching ruin, the less populous of more modern structure, but generally sunk in filth."

Large numbers of Irish immigrants settled in Hulme, and in various other districts of Manchester.

The Tithe award for Hulme was made in 1854. In 1863 members of the Hulme Athenaeum club for working men established an association football club, believed to be the earliest example in the city and in the county of Lancashire. Records of association games in the 1860s and 1870s exist with the club surviving into the early 1870s.

The foundation stone of the first school erected by the Manchester School Board was laid in Vine Street, Hulme, on 11 June 1874 by Herbert Birley, chairman of the board, and the school was opened on 9 August 1875. Other board schools in Hulme were at Hamer Street (1872), Zion Chapel (1875), Lloyd Street (1878), Mulberry Street (1881), Upper Jackson Street (1883), Bangor Street (1886) and Duke Street (1890).

In 1913 it was said "It is probable that in no northern city is the divergence between classes so marked as it is becoming in Manchester. Among the 80,000 inhabitants, for example, of Hulme, the poorest and most neglected district of the city, is to be found only a tiny minority of persons of much education and refinement, these being with rare exceptions doctors, or ministers of the various religious denominations, and their wives"

Courts

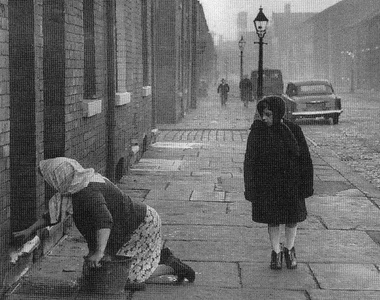

As Hulme developed in the early 19th century many developers tried to fit as many houses as possible on one site. One way in which this was done was to create ' courts '. These consisted of houses built around a square with an entrance at one end and the necessary sanitation facilities in the centre. Although this illustration gives the impression of a court, it is probably not one. The terraces in the background appear to be completely seperate from those on the other side.

Stone street

Sandwiched between the River Medlock, Chester Rd and City Road were numerous streets of poorly constructed houses which were lacking many of the basics essential for healthy living. One of the streets was Stone St, off Pryme St. These properties had been built in an area which was relatively low lying, at the time where there were few controls over what could be built, the quality of building work and where it could be done. This photograph shows what appears to be the demolition work taking place on Stone St at the beginning of the 20th century. Almost certainly these were back-to-back houses, each property having only one fireplace, as indicted by the lack of chimney pots. Notice the shutters still in place on some of the ground floor windows.

kids in Hulme

In the days before Radio and Television one way in which people could hear music was from street musicians. The person in the center of this small crowd of children appears to be playing the accordion and has attracted some interest among the children, while the adults stand at the doors listening and watching the children. The fact that there are men present and children around suggest that the photograph might have been taken on a Sunday morning. Another clue which supports this is the presence of two small birdcages which can be seen to the left of the doorways. The absence of any women suggest they they are either preparing a meal or doing the weekly cleaning, and the birds had been put outside for some fresh air while the housework was being completed. The size of the cages would be criticized today as not allowing the birds enough room to move around but the birds themselves would have livened up a drab house.

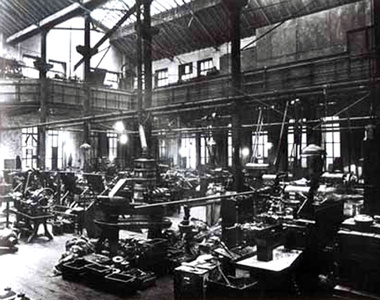

Rolls Royce

In 1904, two businessmen known as Henry Royce and Charles Stewart Rolls created a business partnership after meeting at Manchester's Midland Hotel and decided to start to build their own versions of the relatively new invention of the motor car - and chose Hulme for their first Rolls-Royce factory, though moving to Derby shortly afterwards. Many street names in the current Hulme commemorate this little piece of history, such as Royce Road and Rolls Crescent, though the Royce public house, a popular drinking establishment with a distinctive ceramic historical 'mural' was razed for the creation of modern flats, in the 1990s regeneration of Hulme.

Rolls Royce statue erected a few hundreds yards from where Cooke street once stood, Hulme Park present day

At the end of World War II, Britain had a dramatically high need for quality housing, with a rapidly increasing "baby boomer" population increasingly becoming unhappy with the prewar and wartime "austerity" of their lives, and indeed, their living space. By the start of the 1960s England had begun to remove many of the 19th century 'slums' and consequently, most of the slum areas of Hulme were demolished. The modernist and brutalist architectural style of the period, as well as practicalities of speed and cost of construction dictated high rise "modular" living in tower blocks and "cities in the sky" consisting of deck-access apartments and terraces.

In Hulme, a new and (at the time) innovative design for deck access and tower living was attempted, whereby curved rows of low-rise flats with deck access far above the streets was created, known as the 'Crescents' (which were, ironically, architecturally based on terraced housing in Bath). In this arrangement, motor vehicles remained on ground level with pedestrians on concrete walkways overhead, above the smoke and fumes of the street. High-density housing was balanced with large green spaces and trees below, and the pedestrian had priority on the ground over cars. At the time, the 'Crescents' won several design awards and had some notable first occupants, such as Nico and Alain Delon. However, what eventually turned out be recognised as poor design, workmanship, and maintenance meant that the crescents introduced their own problems. Design flaws and unreliable "system build" construction methods, as well as the 1970s Oil Crisis meant that heating the poorly insulated homes became too expensive for its low income residents, and the crescents soon became notorious for being cold, damp and riddled with cockroaches and other vermin. Reports from local residents of the period also suggest that at this time, a combination of increasing economic hardship, poor maintenance and the Housing Act meant that many tenants who had maintained a sense of civic pride in the area left, as standards went into free fall as a result of the Act. The auspices of the Act allowed anyone claiming state benefits the right to a Council home. As a result, the now notoriously unpopular properties became a "dumping ground" for many of the city's poorest, most deprived, and indeed, anti-social members of society.

As a result, rates of drug addiction and crime soared in the neighbourhood. Local reports suggest that the City Council at one point almost completely lost control of the properties on the estate, and was reduced to handing out keys to properties to anyone who would take them, in order to ensure the use of empty properties. This resulted in a "black market" exchange of properties between squatters, eliminating any possibility of meaningful management of the properties by the council. Local commentators noted that the "neighbourliness" of the previously cramped housing conditions had been eliminated, and due to the "impersonality" of the crescent development any local "sense of community" had also been eliminated. An eventual overspill, and the need for quality housing of the existing communities, meant that large numbers of families were relocated across Greater Manchester, though a many were sent to Wythenshawe, a large "overspill" estate.

Latest Posts